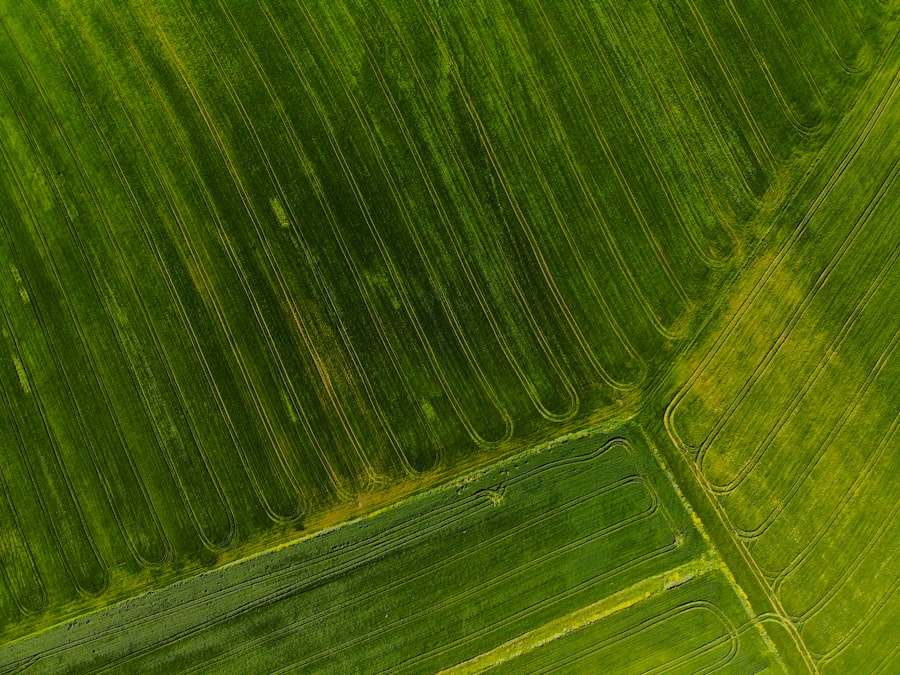

You stand at the precipice of a burgeoning global population, a silent observer of the increasingly strained relationship between humanity and its most fundamental resource: food. As this relationship evolves, so too does the landscape of food production, particularly the ownership and accessibility of the very Earth that sustains us. You may harbor a romanticized notion of the independent farmer, tilling their own soil, a testament to self-sufficiency. However, the reality you face today is a far cry from this idyllic image. The ability to acquire agricultural land, once a cornerstone of prosperity for many, has become a formidable challenge, particularly for the average buyer. You are about to delve into the intricate web of economic, social, and environmental factors that transform farmland into an inaccessible fortress for those without significant capital or established connections.

You will find that the dream of owning a piece of agricultural land, a direct connection to the source of sustenance, remains, for most, just that: a dream. The barriers you will encounter are multifaceted, sometimes overtly prohibitive, and at other times subtly insidious, eroding the very foundations of agricultural accessibility. As you navigate this complex terrain, remember that the implications extend beyond individual aspirations; they touch upon food security, environmental stewardship, and the very fabric of rural communities. The documentary explores the impact of the financialization of American agriculture on rural communities and farming practices.

You might possess a modest savings account, perhaps a nest egg you diligently built over years. You envision this capital as your key to a plot of land, a tangible asset. However, as you begin to research agricultural property listings, you are confronted with a stark reality: the prices are often astronomical, far exceeding the financial capacity of most individuals. This upward trajectory in land value is not a fleeting anomaly; it is a systemic trend, driven by a confluence of powerful forces that effectively lock out the average buyer.

Investment Magnet: Farmland as a Secure Asset

You may recognize the allure of diversified portfolios, of spreading risk across various asset classes. What you might not immediately consider is that farmland has increasingly become a coveted asset for institutional investors, pension funds, and high-net-worth individuals. These entities view agricultural land not merely as a site for food production, but as a stable Store of value, a tangible hedge against inflation and economic volatility.

- Inflationary Hedge: You’ve likely observed the eroding power of inflation on your savings. Farmland, unlike many other assets, often performs well during periods of inflation, as agricultural commodities become more valuable. This inherent resilience makes it an attractive proposition for those seeking to preserve or grow wealth.

- Tangible Asset Appeal: In an increasingly digitized world, the tangibility of land holds a unique appeal. You can’t hack it, it won’t disappear in a market crash (though its value can fluctuate), and it offers a psychological sense of security that abstract investments often lack. This perceived safety draws in capital from individuals and organizations seeking solid ground in volatile financial markets.

- Growing Global Demand for Food: You are acutely aware of the expanding global population. This demographic trend translates directly into an escalating demand for food, which in turn boosts the long-term prospects of agricultural land. Investors, with their long-term horizons, internalize this fundamental demand, viewing farmland as an investment with enduring relevance.

Competition from Non-Agricultural Buyers: A Clash of Values

You might assume that your primary competitors for agricultural land would be other aspiring farmers. However, you are increasingly pitted against a different breed of buyer: those with no intention of cultivating the soil. These non-agricultural buyers, driven by motives often disparate from food production, significantly inflate land values, creating an uneven playing field.

- Residential and Commercial Development: You’ve witnessed the relentless march of suburban sprawl. As urban centers expand, surrounding agricultural land becomes prime real estate for housing developments, shopping centers, and industrial parks. Developers, with their substantially larger capital reserves and profit margins, can offer prices that far outstrip what any farmer could sustainably pay. They see a blank canvas for construction, not a fertile ground for crops.

- Recreational and Lifestyle Buyers: You might dream of a quiet retreat, a place to escape the urban grind. Others share this sentiment, and their vision often includes sprawling rural properties. Wealthy individuals seeking large estates, hunting grounds, or simply a picturesque escape are willing to pay a premium for agricultural land, viewing it as a lifestyle enhancement rather than a productive enterprise. This demand, while understandable, distorts the market for genuine agricultural purposes.

Subsidies and Economic Incentives: Unintended Consequences

You are likely familiar with government subsidies in various sectors. While often designed to support specific industries or achieve particular policy goals, in the context of agriculture, some governmental interventions can inadvertently contribute to elevated land prices, making it harder for new entrants to compete.

- Commodity Price Supports: In some regions, government policies that guarantee minimum prices for certain crops can make farming a more predictable and potentially profitable enterprise. While beneficial for established farmers, these guarantees can also make farmland a more attractive investment, thereby driving up its acquisition cost. You might see this as a safety net, but it simultaneously inflates the cost of entry.

- Conservation Programs: You likely approve of efforts to protect the environment. Government programs that pay landowners to set aside land for conservation, wildlife habitats, or carbon sequestration are laudable. However, these payments can also increase the perceived value of agricultural land, as they represent an additional income stream for owners, potentially pushing purchase prices beyond the reach of those solely focused on traditional farming.

The challenges faced by the average person in purchasing farmland are multifaceted, often stemming from rising land prices, competition from large agricultural corporations, and the complexities of financing such investments. For a deeper understanding of these issues, you can explore a related article that discusses the barriers to farmland ownership and the implications for aspiring farmers and investors alike. To read more, visit this article.

The Financial Labyrinth: Securing Capital in a High-Stakes Game

You’ve accepted that the upfront cost of land is a monumental hurdle. But the financial challenges don’t end there. Even if you manage to secure a deposit, navigating the labyrinthine world of agricultural finance presents its own set of formidable obstacles, particularly for individuals without a long-standing track record in farming.

Limited Access to Traditional Lending: A Catch-22

You’ve probably applied for a mortgage or a business loan at some point. You understand that lenders assess risk. However, when it comes to agricultural land, for someone without inherited land or extensive farming experience, the risk profile often appears unacceptably high to traditional financial institutions.

- Lack of Collateral: You may not possess existing land or substantial assets to use as collateral. For new farmers, this absence of readily acceptable security makes lenders hesitant. They see a higher potential for default with less recourse to recover their investment.

- Unproven Business Plan: You might have a meticulously crafted business plan outlining your agricultural vision. However, without a demonstrated history of successful farming operations, your projections might be viewed with skepticism. Lenders prefer established businesses with verifiable income streams and a proven ability to manage agricultural risks like weather, disease, and market fluctuations. They are risk-averse, and you, as a new entrant, represent an unknown variable.

- Specialized Knowledge Requirement: Agricultural lending often requires a specialized understanding of the unique risks and cycles of farming. Many conventional banks may lack the internal expertise to accurately assess agricultural loan applications, preferring to lend to more familiar business models. This lack of institutional understanding can lead to overly cautious lending practices or outright rejection of deserving proposals.

Onerous Loan Terms and Interest Rates: A Heavy Burden

Even if you manage to secure financing, the terms and conditions often place an unsustainable burden on new farmers. You are not simply paying for land; you are often financing the very tools of your trade, the infrastructure, and the initial operating capital.

- Higher Interest Rates: Due to perceived higher risk, agricultural loans for unproven individuals often come with higher interest rates compared to established businesses or residential mortgages. This higher cost of capital significantly impacts profitability, making it harder to generate sufficient income to service the debt. You are starting with a heavier financial yoke around your neck.

- Short Repayment Periods: Unlike residential mortgages that stretch over decades, agricultural loans for land or equipment may have shorter repayment periods. This necessitates larger monthly or annual payments, creating intense cash flow pressure, particularly in the initial years of operation when income may be inconsistent.

- Down Payment Requirements: You’ve likely encountered the need for a substantial down payment for any large purchase. For agricultural land, these requirements can be particularly high, often 20-30% or more of the purchase price. Accumulating such a significant sum is a formidable task for someone without prior wealth or substantial inheritances.

Lack of Government Support and Innovative Financing: A Patchwork Solution

You might expect robust government programs designed to facilitate entry into farming. While some initiatives exist, they are often insufficient in scale or scope to address the systemic barriers faced by aspiring farmers.

- Limited Grant Opportunities: While grants for beginning farmers do exist, they are typically competitive, limited in number, and often focused on specific projects rather than outright land acquisition. You might spend countless hours applying for these, only to find yourself among a multitude of equally deserving applicants.

- Youth Farmer Programs: Some regions have programs aimed at supporting young farmers. However, these often have strict eligibility criteria, such as age limits or specific educational requirements, and may not cater to individuals seeking a career change later in life or those who learn through practical experience rather than formal education.

- Novel Financing Models: You are increasingly seeing innovative models like land trusts, community-supported agriculture (CSA) models with land access components, or crowdfunded initiatives. While promising, these are often localized, smaller scale, and not yet widely available or capable of addressing the magnitude of the accessibility problem on a national or global scale. They are small streams in a vast desert.

The Knowledge Gap: More Than Just Turning Soil

You might possess a deep passion for farming, a willingness to work hard, and a desire to connect with the land. However, modern agriculture is a complex, science-driven, and business-oriented endeavor. Simply having a green thumb is no longer enough. The lack of readily accessible knowledge and mentorship creates another significant barrier.

Absence of Mentorship and Succession Planning: A Legacy Lost

You might observe that many existing farmers are aging, and their children are often choosing different career paths. This demographic shift, while creating opportunities, also leaves a vacuum of knowledge and experience that is not easily filled.

- Aging Farmer Population: You will find that the average age of farmers in many developed nations is steadily increasing. This points to a potential crisis in succession, where valuable knowledge, techniques, and specific land nuances are not being effectively passed down.

- Difficulty in Finding Mentors: As a new entrant, you benefit immensely from the guidance of experienced farmers. However, finding willing and capable mentors can be challenging. Established farmers may be too busy, or perhaps even wary of new competition in their local markets.

- Limited Apprenticeship Opportunities: Formal apprenticeship programs in agriculture are scarce compared to other trades. This lack of structured, hands-on learning pathways makes it difficult for aspiring farmers to gain the practical skills and confidence needed to manage a farm independently. You’re often left to learn by trial and error, a costly and inefficient method.

The Complexity of Modern Agriculture: A Steep Learning Curve

You might envision farming as a straightforward process of planting seeds and harvesting crops. However, the reality is far more intricate, demanding a diverse skill set that goes beyond basic agronomy.

- Agronomic Science and Technology: You must grapple with soil science, pest management, crop rotation, irrigation, and the ever-evolving landscape of agricultural technology, from precision planting to drone-based monitoring. The knowledge base is vast and constantly expanding.

- Business Management and Marketing: Beyond the fields, you need to be a savvy business person. This includes financial management, marketing strategies, understanding supply chains, managing labor, and complying with a myriad of regulations. You are not just a farmer; you are an entrepreneur, a scientist, and a manager, all rolled into one.

- Regulatory Compliance and Environmental Stewardship: You will face a complex web of environmental regulations, food safety standards, zoning laws, and labor laws. Navigating these requirements, while simultaneously striving for sustainable practices, adds another layer of complexity that can be daunting for someone new to the industry. You must be a legal scholar as well as a farmer.

Bridging the Educational Divide: Accessible and Relevant Training

You might look for educational programs to prepare yourself for this demanding career. While agricultural colleges exist, specialized training tailored for new, non-traditional entrants, particularly those lacking agricultural backgrounds, is often insufficient or inaccessible.

- Cost of Formal Education: Agricultural degrees can be expensive, adding to the already substantial financial burden. For many, a four-year degree may not be feasible or desirable, particularly if they are seeking practical, hands-on skills rather than theoretical knowledge.

- Relevance of Traditional Curricula: You may find that some traditional agricultural programs are geared towards large-scale industrial farming or research, and may not adequately address the specific needs of small-to-medium scale, diversified, or beginning farmers who often prioritize direct market sales and sustainable practices.

- Lack of Practical, Hands-on Training: The most effective agricultural education often involves significant practical experience. However, opportunities for immersive, on-farm training, particularly those that are affordable and structured, are often limited. You need to get your hands dirty, but finding the right place to do so can be difficult.

Infrastructure and Support Systems: The Invisible Hurdles

You might secure the land and even the financing, but your journey is far from over. The surrounding infrastructure, access to essential services, and the strength of the agricultural community itself can either propel you forward or leave you isolated and struggling. These are the often-overlooked practicalities that can tip the balance.

Lack of Affordable Housing and Rural Services: A Desolate Landscape

You may have your heart set on your plot of land, but where will you live? The cost of living in rural areas, particularly for housing, might surprise you, especially if you also need access to essential services that are becoming increasingly scarce in some regions.

- Rural Housing Shortages: You may find that affordable housing options in rural agricultural areas are limited. Existing housing stock may be old, in disrepair, or expensive, reflecting demand from second-home owners or retirees who inflate prices beyond the means of working farmers.

- Dwindling Rural Services: As rural populations decline in some areas, so too do essential services. You might struggle to access reliable internet, affordable childcare, quality healthcare, or even basic repair services for farm equipment. This lack of support infrastructure adds another layer of stress and operational difficulty.

- Transportation Challenges: Getting produce to market, accessing supplies, or even just reaching remote parts of your farm can be challenging in areas with poor road infrastructure or limited public transport. You become dependent on personal vehicles and often face long commutes for essential needs.

Limited Access to Processing and Distribution: The Missing Links

You’ve grown your crops, but what now? The ability to process, package, and distribute your produce effectively is just as crucial as growing it. Without accessible infrastructure, your efforts in the field can be undermined by bottlenecks further down the supply chain.

- Consolidation of Processing Facilities: You may find that local slaughterhouses, creameries, grain elevators, and produce packing facilities have consolidated or closed down, often due to economies of scale. This forces you to transport your products long distances, increasing costs and reducing freshness.

- High Barrier to Entry for Small-Scale Processors: Establishing your own processing facilities often requires significant capital investment and navigating complex regulations. For a new farmer, this is usually an insurmountable hurdle. You cannot simply build your own abattoir or cannery overnight.

- Market Access Challenges: Breaking into established distribution channels, whether through large supermarkets or even regional restaurant networks, can be challenging without pre-existing relationships or significant marketing budgets. You might find yourself locked out of lucrative markets, forced to rely on less profitable direct-to-consumer sales or smaller, local outlets.

Fragmented Producer Networks and Collective Action: The Isolated Farmer

You might feel like an individual actor in a vast, competitive landscape. Without strong, cohesive networks of farmers, you lack the collective bargaining power, shared resources, and mutual support that can be vital for survival and growth.

- Lack of Cooperative Structures: You’ll notice that agricultural cooperatives, once a backbone of many farming communities, have declined in many areas or are primarily geared towards larger, commodity producers. The absence of robust, small-scale cooperatives means you lose opportunities for bulk purchasing, shared equipment, or collective marketing.

- Limited Peer-to-Peer Support: While online forums exist, the irreplaceable value of face-to-face peer support, sharing knowledge over a fence, or borrowing an essential piece of equipment from a neighbor is diminishing as agricultural communities become less interconnected and more spread out. You’re often left to solve problems in isolation.

- Advocacy and Policy Influence: Without strong organizations representing the interests of new and small-scale farmers, your voice is often unheard in policy debates. This means that regulations and support programs may continue to favor established, larger agricultural interests, further entrenching the barriers you face.

The rising cost of farmland has made it increasingly difficult for the average person to enter the agricultural market, as prices continue to soar due to factors such as urbanization and investment trends. For those interested in understanding the broader implications of this issue, a related article discusses the challenges and barriers that prevent individuals from purchasing farmland. You can read more about it in this insightful piece on wealth growth strategies at How Wealth Grows. This resource sheds light on the economic dynamics at play and offers valuable perspectives on the future of land ownership.

Environmental and Social Considerations: Beyond the Economics

| Factor | Description | Impact on Average Person |

|---|---|---|

| High Land Prices | Farmland prices have increased significantly due to demand, investment, and limited supply. | Many cannot afford the upfront cost to purchase farmland. |

| Large Minimum Acreage | Many farms require purchasing large plots of land to be viable. | High total cost and maintenance make it inaccessible for small buyers. |

| Financing Difficulties | Obtaining loans for farmland is challenging due to risk and long-term investment nature. | Average buyers struggle to secure necessary financing. |

| Competition from Investors | Institutional investors and corporations buy farmland as an asset. | Increases prices and reduces availability for individual buyers. |

| Regulatory Restrictions | Zoning laws and agricultural regulations limit land use and ownership. | Complicates purchase and use for non-farmers or small-scale buyers. |

| Maintenance and Operational Costs | Farming requires ongoing investment in equipment, labor, and upkeep. | Financial burden discourages average individuals from buying farmland. |

| Knowledge and Experience | Successful farming requires expertise and time commitment. | Lack of experience deters average people from investing in farmland. |

You are likely driven by a desire to farm sustainably, to be a good steward of the land. However, the environmental challenges and social dynamics of agricultural land ownership introduce another layer of complexity, often making the quest for inaccessible farmland even more daunting.

Climate Change and Resource Scarcity: An Unpredictable Future

You are acutely aware of the changing global climate. This environmental reality directly impacts agricultural land, introducing an element of risk and unpredictability that makes long-term planning and investment even more challenging.

- Water Scarcity and Allocation: You will find that access to reliable water, whether from rainfall, rivers, or aquifers, is increasingly becoming a critical and contentious issue. Droughts are more frequent, and competition for water resources intensifies, making it harder to secure the necessary water rights or ensure consistent supply.

- Soil Degradation and Erosion: You inherit land that may have been subjected to decades of intensive farming practices, leading to depleted soil health, erosion, and reduced fertility. Restoring this soil requires significant investment in time, labor, and resources, adding to your initial operational costs.

- Extreme Weather Events: You face an increased risk of devastating floods, prolonged droughts, unseasonal frosts, or intense heat waves. These events can wipe out entire harvests, destroy infrastructure, and lead to significant financial losses, making agricultural investment inherently riskier. Insurance can mitigate some risks, but it cannot replace the lost yield.

Land Use Conflicts and Community Resistance: An Unwelcome Neighbor

You might envision integrating seamlessly into a rural community. However, new agricultural ventures can sometimes face unexpected resistance from established residents, particularly if your farming practices differ from the norm or if you are perceived as an outsider.

- “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBYism): You might propose a particular type of farming – perhaps organic, direct-to-consumer, or even agritourism – that residents in established rural communities view with skepticism or outright opposition. Concerns about traffic, noise, aesthetics, or impact on property values can lead to planning disputes and social friction.

- Cultural and Social Integration: You may encounter established social norms and expectations that are resistant to change. Gaining acceptance and building trust in a close-knit rural community can take time and effort, and you might initially feel like an interloper.

- Competition for Resources: You might find yourself competing with existing farmers for access to labor, local processing facilities, or even specific market niches, which can sometimes lead to resentment if not managed carefully.

Loss of Agricultural Land to Other Uses: A Shrinking Pie

You are seeking a piece of the agricultural pie, but that pie is continually shrinking. The relentless conversion of farmland for urban expansion, infrastructure projects, and other non-agricultural uses exacerbates the scarcity and further drives up land values, making your quest even more difficult.

- Urban Sprawl and Infrastructure Development: You will observe that cities and towns relentlessly expand, consuming prime agricultural land for housing estates, commercial centers, and transportation networks. Once converted, this land is almost impossible to revert to agricultural use.

- Renewable Energy Projects: While vital for addressing climate change, large-scale solar farms and wind turbine installations also require significant land areas, often in rural settings. While these projects offer lease payments to landowners, they remove productive land from agricultural use, adding to the cumulative pressure on the available supply.

- Timber and Mining Interests: You may find agricultural land that is also desirable for its timber resources or underlying mineral deposits. These industries, operating with different economic models and often larger capital, can outbid agricultural buyers, especially in areas where agriculture is marginally profitable.

You have now journeyed through the multifaceted landscape of challenges that render agricultural land largely inaccessible to the average buyer. You’ve seen how economic forces, financial hurdles, knowledge gaps, infrastructural deficiencies, and complex environmental and social considerations coalesce to form an impenetrable wall. The romanticized image of the accessible family farm recedes further into the past, replaced by a complex reality where land is increasingly a speculative asset, a battleground for competing interests, and a precious resource under immense pressure. For you, the average buyer, the path to agricultural land ownership is not simply steep; it is often blocked by a series of formidable, interconnected barriers that demand innovative solutions, significant policy shifts, and a fundamental re-evaluation of how we value and manage the very ground beneath our feet.

WATCH THIS! ⚠️💰🌾 Why Wall Street Is Buying Up America’s Farmland (And Why It Should Terrify You)

FAQs

Why is farmland often expensive for the average person?

Farmland prices are typically high due to limited availability, increasing demand from investors and commercial agriculture, and the costs associated with maintaining and improving the land. Additionally, farmland is considered a valuable long-term investment, which drives prices upward.

Are there legal restrictions that prevent average people from buying farmland?

In some regions, there are zoning laws, land use regulations, or restrictions on foreign ownership that can limit who can purchase farmland. These laws vary by country and locality and may affect the ability of average individuals to buy farmland.

Do financing challenges affect the ability of average people to buy farmland?

Yes, obtaining financing for farmland can be difficult for average buyers. Lenders often require substantial down payments, proof of farming experience, or a strong credit history. Interest rates and loan terms for agricultural land can also be less favorable compared to residential properties.

Is farmland ownership typically limited to experienced farmers or investors?

Often, farmland is purchased by experienced farmers, agribusinesses, or investors who understand the agricultural market and can manage the land effectively. Lack of farming knowledge or experience can be a barrier for average individuals interested in buying farmland.

How does competition from large agribusinesses impact farmland availability?

Large agribusinesses and institutional investors frequently buy farmland in bulk, which reduces the amount of land available for individual buyers. Their financial resources allow them to outbid average buyers, making it harder for individuals to purchase farmland.

Are there alternative ways for average people to invest in farmland?

Yes, alternatives include investing in farmland through real estate investment trusts (REITs), agricultural funds, or community-supported agriculture programs. These options allow individuals to gain exposure to farmland without directly purchasing and managing the land.